Sincerity In Calligraphy

“Religious images and statements are not under our control. They are psychic events… charged with such intense numinosity that they are described as separate from their transcendent object. Statements and images do not question the reality of the transcendent object (as claimed by the accusation of psychologism); they interpret them.”

—Henry Corbin, “The Eternal Sophia”

Background

This Arabic calligraphy project which I just completed is a rendering of the famous chapter of the Qur’an titled surah al-Ikhlāṣ (tr: the chapter of sincerity). This short chapter contains only four verses, but is widely considered as the most succinct and profound declaration of Islamic monotheism. The words of surah al-Ikhlāṣ are very frequently recited by Muslims, both within the context of the central religious practice of salah (the five daily prayers), and within more mystical contexts of Sufi dhikr—recitations performed for the remembrance of God.

Here is a translation of surah al-Ikhlāṣ:

قُلْ هُوَ ٱللَّهُ أَحَدٌ

Qul huwa l-lāhu ’aḥad

Say: He is God, the One

ٱللَّهُ ٱلصَّمَدُ

‘Allāhu ṣ-ṣamad

God, the Everlasting Refuge

لَمْ يَلِدْ وَلَمْ يُولَدْ

Lam yalid walam yūlad

He begets not, nor was He begotten

وَلَمْ يَكُن لَّهُۥ كُفُوًا أَحَدٌۢ

Walam yaku n-lahū kufuwan ’aḥad

And there is none comparable unto Him

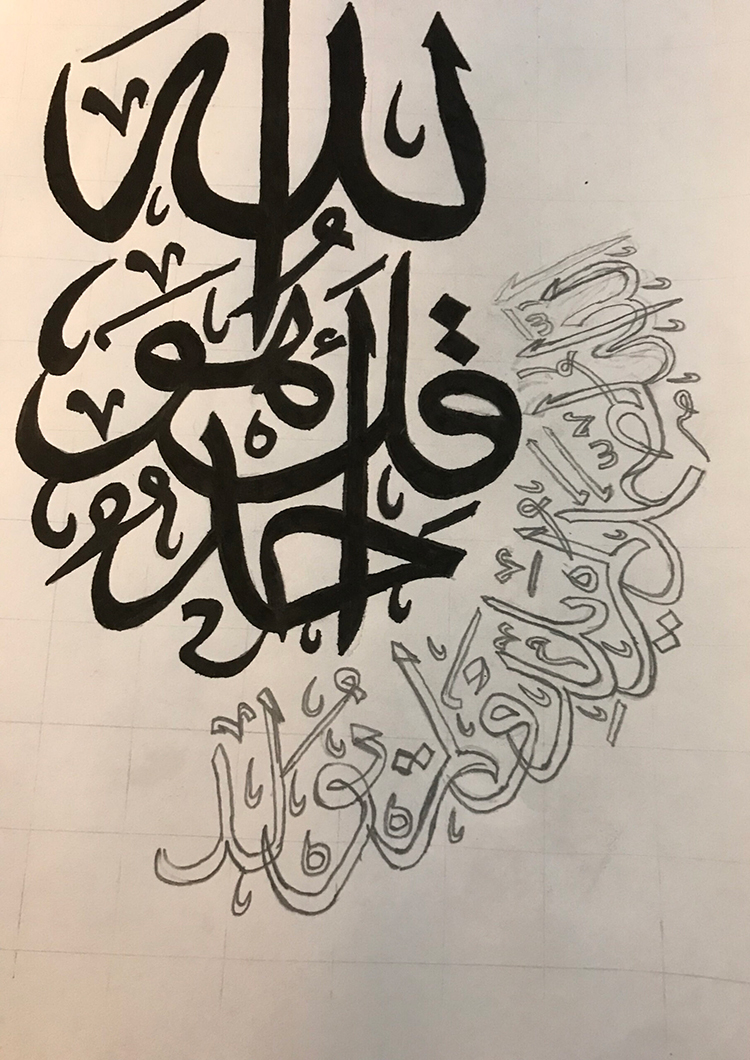

In this piece, the first verse of the surah is featured in the center of the image, with the following three verses wrapping around this text. The Arabic name of God (Allah, ﷲ) features prominently at the top of the piece, symbolically showing God’s Lordship over all things.

Process

This work is the result of endeavoring to faithfully copy a great work of Islamic calligraphy. As someone with minimal familiarity with the Arabic language and no formal artistic training, creating an original piece of calligraphy in Arabic would be extremely difficult. I am, however, very inspired by the aesthetics of Islamic calligraphy (of which there are many styles) and have previously recreated some simpler works with a less formal process.

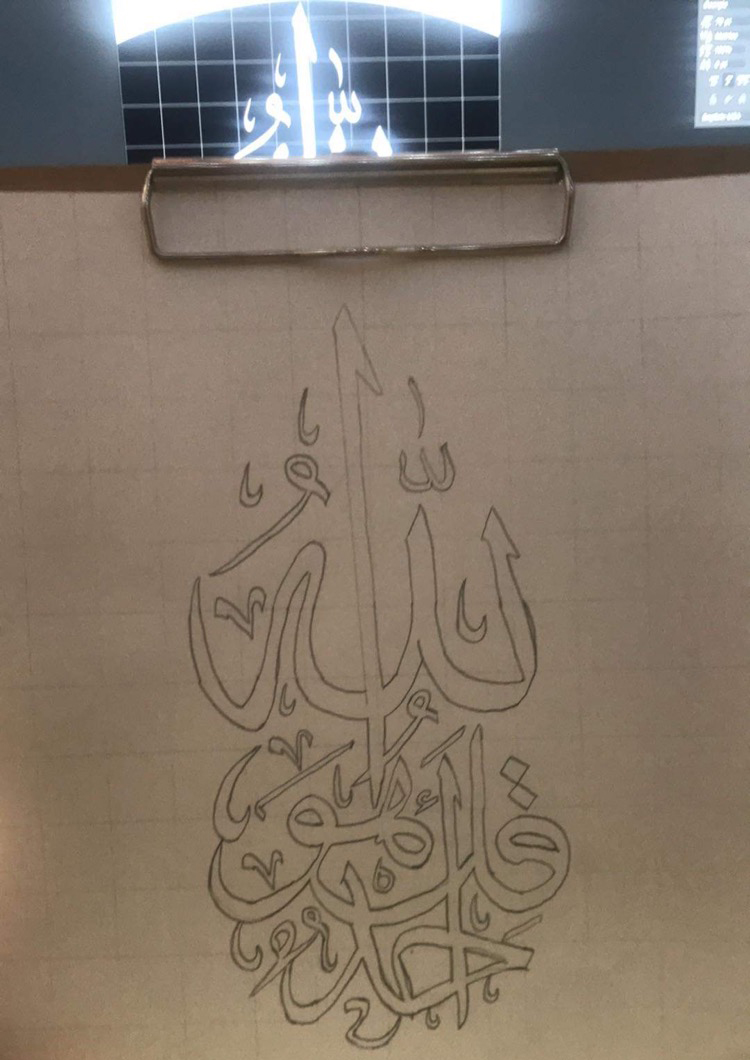

Knowing I really wanted to do this work justice, but lacking any of the requisite tools for proper calligraphy, I resorted to a method I remember learning in middle school. The technique—which is meant for reproducing images at different scales—involves overlaying a grid on a source image, and then recreating a grid with the same dimensions on your canvas. This allows you to immediately see the proportions of the original image and reconstruct it in manageable chunks. If you look closely at some of the process photos, you will be able to see a grid on the page which I penciled on and then erased when the work was complete. So, to get started I would reference the original image I had importanted into photoshop, and see where the strokes for the various letters intersected in a given square in the grid. From there, I was able to begin reproducing the outlines of the letters in pencil.

After I had completed the pencil outlines, I used a fountain pen with Noodler’s X-Feather Black ink to trace these lines with precision. For this, I used a pen with a fine nib, to allow for slender and clean lines. Once these outlines were complete, however, I still needed to fill the characters in with black ink. For this I used a fountain pen with a broad nib, which allowed me to more quickly cover the white space in ink.

I did not wait to completely finish the pencil outline before I began finalizing parts of the work with pen. I ended up splitting the work into three sessions where I took a section of the piece from beginning to completion.

I found the process of creating this work to be rather demanding. A high degree of precision was involved, both in perception in order to begin accurately reproducing the piece, but also with the strokes themselves, especially in the final pass with pen. While my method was not traditional to the medium, it did allow me to reproduce this incredible work with a high degree of accuracy despite my lack of training. Ultimately, I believe the traditional method of Arabic calligraphy which uses reed pens would allow for a quicker and more fluid execution of this piece, but there’s a steep learning curve for such techniques and true learning would likely require instruction from a master.

Conclusion

Producing a work of religious art like this calligraphy of surah al-Ikhlāṣ requires significant focus, patience, and rigor. The artistic process itself has a certain meditative or contemplative character, as you are not merely reproducing some representational imagery, but you are engaged in a kind of deep symbolurgy as you take religious realities from the ether and provide them with a concrete material form in the world of sense perceptions. A great work of religious art is like a vehicle of sorts—it can transport you from the everyday world into relationships with the sacred and the Divine. But here there is no concrete destination, no single discrete reality to which a given work of religious art points and which exhausts the work. Encountering a work of religious art is always a process, as you aren’t certain where it will lead you, and bringing different interpretations to the work takes you in different directions and shows different aspects of the Divine reality in which it participates.

This interpretive encounter with the work of religious art is necessarily transformational, which is why sacred art has always been such an essential feature of liturgical practices and individual modes of prayer across world religions. As you enter into relationship with a piece of sacred art, various modes of intuition and contemplation are activated, as these are what are demanded from symbols—at least if you are serious about encountering the realities in which they participate.

Surah al-Ikhlāṣ is an expression of transcendence and majesty, and the regal, bold forms of the Arabic letters in this piece convey these attributes of God on an intuitive level. But there is also a certain intimacy which is expressed in this chapter. God is aṣ-Ṣamad, the Eternal Refuge, meaning that for all our faults and shortcomings, God is always available in His perfection as a place of rest and tranquility. This aspect of the Divine is brought out in this piece through the wrap-around text, which has the character of an all-encompassing embrace. What is remarkable is that these two poles of transcendence (God’s perfection and majesty) and immanence (His being the Eternal Refuge) are presented in perfect harmony and coherence in this piece.

Whereas in human language, things like God’s transcendence and His immanence, or His power and His compassion, may seem opposed to one another, creating a tension within God’s existence. In sacred art, however, these tensions fade away, or are expressed on a deeper level. Metaphysical paradox can be something incredibly productive to ponder, but for this to be the case it is necessary to have a very specific intellectual disposition and a patience for uncertainty in matters of religion. Religious art, on the other hand, presents a more immediate and less cerebral engagement with the same sacred realities, opening up religious insight and intuition in all who dare to encounter the symbols earnestly with their whole being.

In the words of the Prophet (ﷺ) “God is beautiful and He loves beauty.” Routes to God are available for those who cherish beauty in all its forms.

The text of the Qur’an reveals human language crushed by the power of the Divine Word. It is as if human language were scattered into a thousand fragments like a wave scattered into drops against the rocks at sea. One feels through the shattering effect left upon the language of the Qur’an, the power of the Divine whence it originated. The Qur’an displays human language with all the weakness inherent in it becoming suddenly the recipient of the Divine Word and displaying its frailty before a power which is infinitely greater than one can imagine.”

—Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Ideals and Realities of Islam